In order for the UK to meet its net zero carbon target by 2050, the Committee on Climate Change has highlighted that a transformation is required in the scale and speed of energy and carbon reductions from buildings, supported by a robust policy framework.

Meeting the UK’s carbon objectives could also deliver numerous benefits including air quality, health, comfort, productivity, wellbeing, reductions in fuel poverty, as well as job creation, innovation, attracting investment, and opportunities for export of products and services.

Building upon the experience gained through voluntary drivers and theoretical asset ratings, it is clear that policy must address operational performance: buildings should be judged on how they actually perform.

As organisations that represent many key players within the built environment sector, we have all demonstrated a strong commitment to addressing climate change. This provides leadership, but cannot alone achieve the required sector-wide transformation. We have therefore come together to collectively ask for the following:

- The operational performance of buildings should be subject to regulatory requirements. The legislative framework should be amended to capture all opportunities where building performance can be influenced and improved i.e. the construction of new buildings, works to existing buildings, sales, and new or renewed leases.

- In the first instance, regulatory requirements should as a minimum cover energy consumption and carbon emissions. In the near future, they should be expanded to cover other aspects of building performance, including indoor air quality and thermal comfort.

- The public sector should adopt operational building performance minimum requirementsnow in order to demonstrate its commitment, help build industry capacity, and improve the performance of its estate.

- Government should require building performance disclosure and support the necessary infrastructure to underpin it, including appropriate methodologies for assessing and reporting performance, and a commitment to transparency so that performance data can be publicly accessed and analysed.

We would welcome the opportunity to work with Government on the creation and implementation of such a system.

What can you do?

Give us your support! We are keen to accrue support for our position statement from individuals and organisations. If you would like to lend yours, we would like to hear from you. Please contact Laura Morgan Forster: laura@building-performance.network with queries or simply your name and, if appropriate, the organisation you represent.

Background

Why the current regulatory framework is insufficient to deliver actual building performance

The two main current legislative instruments intending to address the energy and carbon performance of buildings are unsatisfactory to deliver the required scale and pace of improvement:

- Building Regulations Part L: the reasons for a disconnect between actual building performance and that calculated under Part L approved methodologies are multiple and well-documented. Chiefly, they include: limitations in methodology; addressing only part of buildings’ energy use and carbon-related emissions (i.e.) heating, domestic hot water, cooling, ventilation, and lighting); and being restricted through the Building Act to building works only i.e. ending at “practical completion”, rather than extending into the in-use stage.

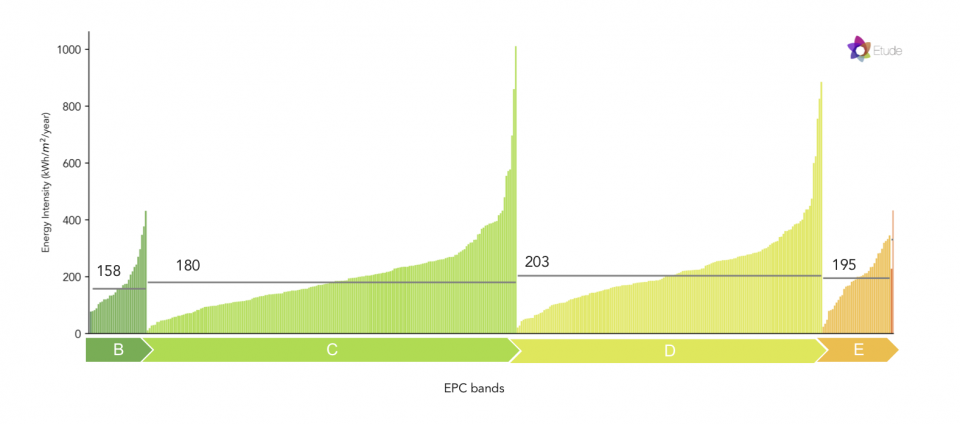

- Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs), which are relied upon in incentives and regulations such as Minimum Energy Efficiencies Standards. Again , it is well-documented that EPC ratings bear little relation to actual energy consumption., as illustrated below.

Figure 1: Illustration of disconnect between EPC bands and actual energy consumption in the office sector: Energy intensity of office buildings, by EPC rating. Each grey bar represents a single office building’s energy intensity over the course of a year (credit: Better Buildings Partnership)

Figure 2: Illustration of disconnect between EPC bands and actual energy consumption in the domestic sector: Energy intensity of 410 homes across a local authority in England, by ECP rating. Each bar represents a single dwelling’s energy intensity over the course of a year (credit: Etude)

Display Energy Certificates (DECs) do cover operational energy performance. However, they are currently only mandated for public buildings (with a consultation expected in 2020 to extend their application to other non-domestic buildings), and the requirements are only for disclosure, not for a particular performance level to be achieved.

A similar lack of comprehensive regulatory framework is found on embodied carbon and in other building performance areas, notably daylight, air quality and thermal comfort, with detrimental effects on occupants’ health, comfort, wellbeing and productivity.

By contrast, there is also ample evidence that setting and verifying operational targets is a crucial part of achieving best practice performance and of closing the performance gap between design intentions, as-built quality and operational performance1. As an added benefit, it also provides more flexibility on design, calculation, and construction methods, as the focus then becomes the best way to deliver the desired outcome.

The need for a regulatory framework

A number of voluntary industry initiatives are available to encourage building performance, monitoring and disclosure. Many of these are led by the signatories to this position statement, and they will continue to drive market leaders2.

However, they cannot on their own deliver the required extent and speed of change which a stable and comprehensive regulatory framework would; as a result, nor can they achieve the same efficiencies of scale and the same distribution of benefits throughout different parts of the population.

A regulatory framework is required, which should include:

- All building sectors

- Compliance and enforcement mechanisms

- Methodologies for assessing and reporting on performance

- A common data framework

- Incentives for early adopters and for going beyond regulatory minima

- Broader legislative provisions, addressing issues such as defining the responsible parties for building performance, and how to safeguard reasonable expectations of anonymity and privacy for building owners and occupants.

Legislative options to allow the introduction of operational performance requirements should be reviewed as a matter of priority. We have identified the following potential avenues which could be explored by government; other options may be available:

- Modifying the Building Act to expand the scope of Building Regulations to the operational stage. It is expected that modifications to the Building Act will be required as part of the implementation of the Hackitt review: this presents a clear opportunity to address other aspects of safety and consumer protection, such as buildings’ energy consumption, carbon emissions, resilience to climate change, and indoor environments3.

- Modifying the Energy Performance of Buildings Regulations, to cover operational building performance beyond current requirements for DECs in public buildings and for air- conditioning inspections.

- For homes, including operational energy performance in the scope of the proposed New Homes Ombudsman and Code of Practice for developers4.

These require further research before definite conclusions can be drawn about the best way to introduce operational performance requirements. The presumption should be that this is possible, at least for the very large majority of buildings, and the focus should be on establishing the most straightforward route and announcing this as the regulatory trajectory at the earliest opportunity to incentivise early adopters.

1 http://www.constructionleadershipcouncil.co.uk/workstream/sustainability/ Buildings Energy Mission report and recommendations, 2019

2 For example: UK-GBC Climate Commitment Platform and Climate Leadership Model, RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, BBP Real Estate Environmental Benchmark (REEB) and Member Climate Change Commitment, CIBSE Climate Action Planand energy benchmarking tool, LETI, Building Performance Network

3 See for example more details on the rationale for this in the BPN’s open letter to the CCC, 2019, and in the CIBSE position paper on the route to net zero carbon buildings

4 See for example more detailed suggestions in the 2019 CIBSE response to the Homes Ombudsman consultation